Hand cutting cane in the La Favorite cane fields, Martinique, 2019.

Understanding Rhum Agricole - An overview of the style and art of pure cane juice distillates from around the world

This article was originally published in Ohana Magazine, 2022 edition, for the Fraternal Order of Moai.

So, your friend hands you a box with a spigot, a glass, a slice of lime and some crystalized raw sugar. She cheerfully exclaims “chacun prepare sa propre mort” and grins. You, not wanting to miss out but not understanding what was just said other than something about death, you put the ingredients into the glass, swirl, and taste it. Ohhhh, you think, Okay. I think I can get used to this.

What just happened? Well, my friend, you just had your first ti’ punch, and were introduced to one of the best ways to understand rhum agricole. Life will be better from now on, armed as you are with the key to this sugarcane kingdom. Since we’ve opened the door, let’s take advantage of our chance to really get acquainted with what rhum agricole is.

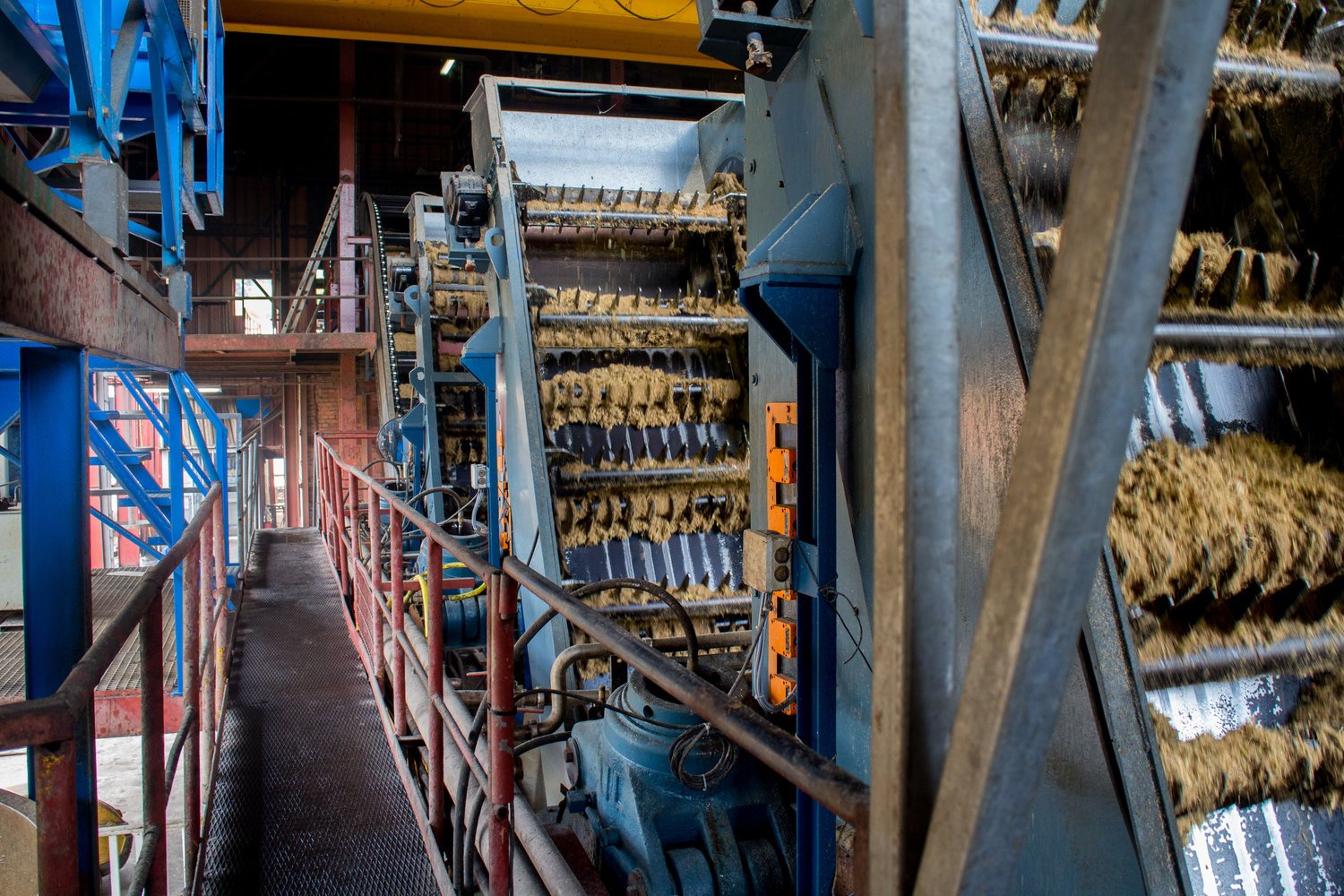

Cane crusher at Maison La Mauny

Rhum agricole, in the most simple terms, is the alcoholic spirit that results when fermented sugar cane juice is distilled. Sugar cane juice is the liquid inside sugar cane, a large, robust plant in the Poaceae (IPA: /poʊˈeɪsiaɪ/) family which resembles bamboo. When put through a grinding mill, sugar cane releases an extremely sweet and sticky liquid. In order to make granulated sugar, the sugar cane juice must be boiled and the sugar crystals that form must be collected. After a long period of boiling the cane juice and removing the crystalized sugar, the viscous substance that is left behind is molasses, which is the base material of many of the rums we are familiar with. Rhum agricoles, by contrast, are made from the extracted juice itself, without having undergone this heating process. Rums made from molasses obviously have a very different character than rums made from freshly crushed cane juice that has not been heated. The idea is that the molasses has endured an “industrial” process (or at least a chemical one), while the crushed cane juice has not. This concept may be a bit of a stretch, but these are the terms that were landed on; industriel (French for industrial) for rum with molasses as a base product, and agricole (agricultural) for rum from sugar cane juice. Another term coming into broader usage for the production category at large is pur jus (in English, pure juice), indicating a rum made from sugar cane juice, but not necessarily adherent to stricter requirements upheld in some regions.

While there is of course a long and deliciously interesting history of sugar cane and its cultivation around the world, from the ancient far east over 8,000 years ago to its arrival in the Caribbean sea in the 15th century, for the purposes of this article we’ll skip over that (well, perhaps at least until you find me gloriously in my cups on a Saturday night at Ohana and ply me with just one more glass). It is sufficient to know that sugar cane is a huge world crop; approximately 1.9 billion metric tons of sugar cane were grown in 2020. Of course, only a tiny percentage of that becomes rhum agricole; the vast majority of it becomes our old standby, table sugar, and is in almost every processed thing we eat and drink.

Franck Dormoy of La Favorite illustrates cane nodules and how cane planting works

How Pur Jus rhums and Rhum Agricoles are Made

Cane is planted by holding back some of the cut stalks from the previous year’s harvest and then planting them in long trenched rows spaced approximately 5 feet apart. Each nodule of the cane stalk can propagate, sending up several new shoots from each piece of cane. These grow into a tall, thick and dense stalk. The harvest season on Martinique is limited from January 1st to August 31st of each crop year; the distillation must be completed by September 5th of that year. Sugar cane overwinters after harvest and lasts from 3-5 growing seasons depending on the harvest method. In fields that are harvested by tractors, the plants only tend to last three years, maybe four in some cases, but when the cane is harvested by hand those plants can go for five years before the field will need to be rotated to a different crop or left fallow to rest. Machine cut stalks are chopped by the machinery into pieces that are 1 foot long. Cane cut by hand remains intact and can be up to twenty feet tall! The cane must have a Brix (sugar content) level of at least 14 before it can be cut, according to the rules defined by the AOC, which we will discuss in more detail shortly.

Once the cane is cut, it is driven by truck to the distillery where it is cracked and crushed by a large, multi towered moulin, or cane mill. Water is added as the cane goes through a series of mills on the crushing equipment. The water allows each subsequent pressing to extract even more of the sugar cane juice and for the machine to work extremely efficiently. The resulting pulp at the end of the crushing process is called bagasse, and it is often burned in the furnaces which run the boilers that create steam to run the stills. The Caribbean is very hot and humid, and once cane is cut it can spoil very quickly; as a result, most distillers aim to have all cut cane crushed and filtered within 24 hours of harvest. Hand cut cane has a slightly longer processing window.

The filtered cane juice and water solution is immediately pumped into fermentation tanks. Yeast is added, and the mixture is left to ferment. Most rhum agricole is fermented for about 72 hours, until the alcohol by volume content (ABV) of the wine is around 3.5-4%, although it can be up to 7.5%. Under Martinique AOC regulations, the fermentation can go up to 120 hours (six days), but producers almost never do this. It is worth noting that this fermentation time is much shorter than molasses rums that can take 12-14 days (and in Jamaica for high ester rums sometimes as long as 3 weeks). The term wine is used in French-speaking rum producing regions to describe the product at this fermented stage - it is the same as wash, or beer, or other equivalent concepts in whisky production. This sugar cane wine is then distilled. In Martinique, a rhum agricole with the AOC distinction on its label must be made on a column still with particular specs. Rhums in Guadeloupe may use a pot still or a column still under their GI and still be called rhum agricole. If that sounds confusing - and to many it is - then let’s brush away some of the dust and talk some more about geographic indications and the infamous Martinique Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (the AOC).

What is L'Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC)?

An AOC is a French certification granted to certain agricultural products. As the name indicates, it is a certification based on origin, and its rules are decided upon by a specially selected committee made up of prominent producers in the style. They together discuss and decide what the identifying characteristics are of the product or group of products in question, taking into consideration region, cultivation, production, aging and finishing, taste, appearance and packaging, while keeping tradition and a sense of the local terroir at the forefront of their deliberations. Once these rules have been mutually approved by the committee, a product must prove that it meets the guidelines to have the AOC marque on its packaging. Consumers who see this symbol or the words appellation d'origine contrôlée on the label will then know that the item they are purchasing meets the requirements (and therefore is certified to have the quality and taste they expect). Many of the famous regional specialties we associate with France are protected by an AOC. The origins of this kind of geographic protectional thinking go back pretty far - Roquefort cheese was first protected by a Parliamentary decree in 1411, and became the first recipient of an AOC for cheese in 1925. Other well known French products with their own AOCs include Poulet de Bresse, Le Puy lentils, Brie, Comté, and Camembert cheeses, Cognac, Armagnac, Calvados, and over 400 French wines, including, naturally, Champagne. Martinique is the only French overseas department to have been granted the distinction of an AOC. That fact alone speaks volumes about the specialness of the pur jus rhums made on the island. The Rhum de la Martinique AOC was first written in 1996, and has been modified a few times since; in 2004, again in 2014, and most recently in December of 2020 (to expand the allowed parcels of land).

There are a few key takeaways here. The first is that AOCs are a uniquely French thing, although other countries of course have their own regulations about protecting wine, cheese, distilled spirits and other regional specialties. The second is that while the idea isn’t a new one, the AOC that dictates what makes a Martinique AOC rhum qualify as such is relatively new, and those rules have been changed several times over the last few decades. These rules are absolutely there to protect a specific regional style and its legacy, but they weren’t handed down on the tablets given to Moses. The third is that these rules apply uniquely to pur jus distillates made on the French island of Martinique (with other similar but different rules that apply to other French departments, and Madeira, but that’s a story for a different day). There is nothing here that says that agricole rum cannot be made elsewhere, or that it cannot be called agricole. True, it can’t be an Rhum Agricole de la Martinique with the AOC distinction, but then there are plenty of agricoles made on Martinique that can’t be called that either, as we will see below.

So, what does that mean for Martinique AOC Rhum?

In order for a cane juice rhum made in Martinique to carry the AOC distinction on its label, it must meet multiple criteria. Each new release by a distillery must be verified by the council before the rhum can be sold. The criteria are:

The rhum must be made from fresh cane grown on an approved parcel on the island of Martinique;

Cane must be harvested between January and August and have a minimum brix level of 14 and ph of 4.7 when cut;

Fermentation must be discontinuous and carried out in open tanks no larger than 500 hectolitres;

The rhum must be distilled on a column still with between 5-9 copper concentration trays. The rest of the still may be made from copper or stainless steel;

The ABV of the distillate may not exceed 75%;

The final ABV of the finished product must be at least 40%;

"Blanc" agricole rums are colorless and must rest in vats for minimum 6 weeks after distillation;

The agricole rhums “élevé sous bois” are placed in oak containers and must be aged for at least twelve months, starting at the fill of the container;

"Vieux" agricole rums are aged in oak containers with a capacity of less than 650 liters for at least three years, starting at the fill of the container;

"Vieux" agricole rums for which the vintage of the distillation year is claimed (also known as vintages) are aged in oak containers with a capacity of less than 650 liters for at least six years, starting at the fill of the container;

The minimum durations defined above are carried out without interruption, with the exception of necessary manipulations for the development of the products.

If a rhum meets all of these requirements and is certified by the AOC board, then it can be sold with the AOC marque on its packaging. There is no requirement that any producer manufacture only rhums with the AOC distinction, although many do. Still, it isn’t unusual for a well known brand to experiment at different stages of production and end up with a delicious, marketable product that doesn’t meet the AOC requirements. The biggest arena where this sort of innovation has been known to be employed is at the finishing stage. As you have seen above, any aging done to an AOC agricole on Martinique must be in oak. American oak (usually once used Bourbon casks) or French oak (either Cognac casks or virgin French oak charred to specific specs) are the most common. Still, there are scores of other types of tropical hardwood that can impart a universe of different flavors to the spirits within. Acacia is a common tropical hardwood used to age cachaça and gives a very unique finish; Maison la Mauny released a limited edition rhum agricole with an acacia finish in 2017. It’s absolutely stunning, and every inch a rhum agricole - but it can’t have an AOC stamp because of the non-oak finish. There are other instances when a rhum wouldn’t qualify for the AOC: using a pot still on Martinique, for instance, as in the ethereal rhums made by A1710; having a shorter aging time in wood than specified; adding flavor to the rhum (pineapple coconut, etc); or sometimes just needing to get a product to market and not having time to go through the AOC approval process.

What about other Agricole or pur jus rhums?

At this point you’ve got a fairly good handle on pur jus rhums from Martinique, but what about sugar cane juice rums from elsewhere? As I’m sure you know, agricoles are made all over the world. We tend to think of them as being uniquely from the French Antilles, and happily, as of January 2015, certain French rhums from the outre-mer did receive GIs (Geographic Indications; in French IG - Indication géographique) outlining their style rules and production techniques as the AOC does in Martinique. Guadeloupe, an archipelago of islands about 150 nautical miles to the north is also a well known agricole region, and its GI was registered in 2008 with the European Parliament. Many of the production methods outlined are reminiscent of Martinique’s AOC, but a primary difference is that both continuous column stills and batch (pot) stills are permitted. It is similar in other French rum producing regions, such as La Reunion & Guyane (French Guiana, not to be confused with Guyana, famous for Demerara rum). Moving further afield of these French departments, rhums made from fresh cane juice can be found in many places where cane is grown. The recent popularity of pur jus distillates in the bartending and rum enthusiast communities has spurred much innovation and excitement about the agricole style. These days, we’re seeing some exquisite pur jus distillates coming from Louisiana and Hawai’i, Mexico, Australia, and French Polynesia. It’s an exciting time for the category. These rhums are calling themselves agricoles, and are well within their rights to do so. I was especially impressed with a recent tasting of Three Roll Estate Agricole from Baton Rouge, Louisiana; it is a beautiful and technically excellent representation of the style. On O’ahu, Kō Hana Distillers are making agricoles from Hawai’ian heritage cane varietals, which are not only delicious and interesting but have a preservation interest in mind. Husk Distillers, located at the very northern edge of New South Wales in the charmingly named town of North Tumblegum, is making a wonderful Australian agricole that has won numerous gold medals and Best of Class/Best of Category distinctions over the last 5 years. Paranubes Rum, an unaged Oaxacan pur jus distillate, humbly calls itself only aguardiente de caña, a Spanish language catch-all term for cane distillates in general that historically was applied to, well, not the best stuff. But don’t the term fool you. Paranubes is elegant, cane forward, with just the right amount of funk and presence - in short, one of the sexiest Mexican rums I’ve tasted in a long, long time.

So there you have it. If I have done my job correctly with this article, you’re excited about sugar cane distillates now and have the tools to find them. If you’d like to learn more about agricole, including reading a full English translation of the text of the Martinique AOC, check out my website at https://rum.academy/blog. Santé!